SATS Principal Kevin Smith, and Faculty member and PhD student Batanayi Manyika, will be presenting a paper at the SBL conference at The Humboldt University of Berlin this week, entitled ‘An analysis of Eschatology in Philemon “ἅμα δὲ καὶ ἑτοίμαζέμοι ξενίαν” for a Southern African context”. Batanayi (or Bat, as he is familiarly called) is currently completing his thesis on the Paul’s letter to Philemon and the interrelationship between Paul, Onesimus (the slave, a Christian convert) and Philemon (the master, Onesimus’ erstwhile “owner”). The focus of the paper, however, is on the hospitality aspects of the letter.

“First century hospitality customs can provide a window through which ancient social identity is observed. When these symbols are analysed against the backdrop of implied eschatology in the letter to Philemon, there emerges a composite picture that interweaves theological discourse with first century cultural norms,” Batanayi writes. “The implicit change of status for Onesimus, and the honour garnered, forms a departure point for Southern Africa, as implications of what was exclusively reserved for social equals are appropriated in a context gripped by chronic social disparity. In this appropriation, unjust legacies are evaluated with the aim of reimaging a context built on equity and justice.”

SATS chatted to Batanayi ahead of the conference about the topic.

SATS: What motivated you to choose the Paul’s letter to Philemon for your thesis?

BM: Often, when people read Paul’s letter to Philemon, they read it from the perspective of the cultural norms of the time, which offer an altered reality to what we experience today. However, the Word of God is alive and active, and so Philemon is a Word for us and Paul’s letter is current and pertinent. Whenever there is a situation where there is a misappropriation of identity, Philemon is a voice that speaks to such a situation.

Hospitality and its practice in the home played a major role in the early Christian life. In Jesus’ time, one’s social status and relationship with the Host would determine where a guest would be seated. We see Peter’s concern, for example, at John’s reclining against Jesus’ chest at the last supper. As he was the most senior of the disciples, this privilege would normally be reserved for him. However, it was John that was given the place of greater honour.

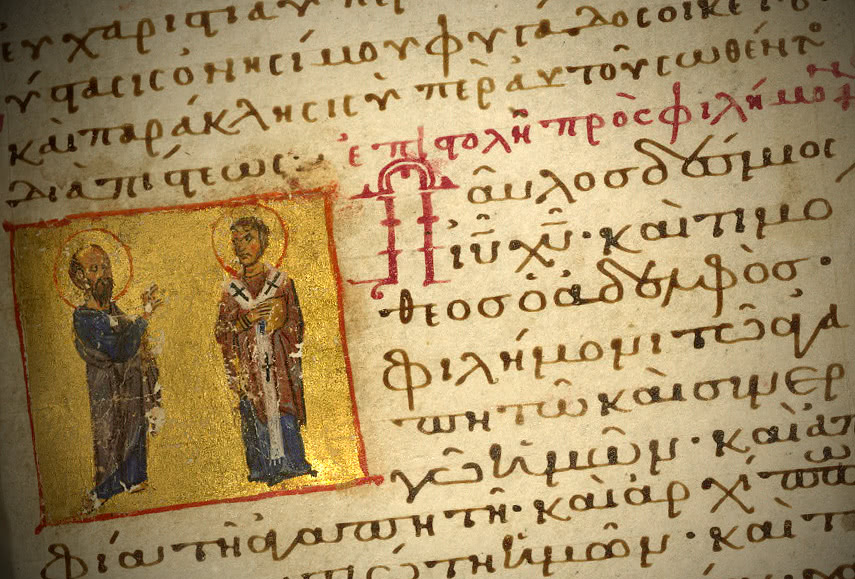

Paul’s letter to Philemon, a noble man, is steeped in references to the cultural norms of the time. Written in elegant Asian rhetorical style so prevalent in Paul’s day, Paul writes not as a social equal, nor as an apostle, but rather as a prisoner in chains entreating Philemon to take Onesimus back, who meanwhile become a Christian. In doing so, he identifies with Onesimus’ status as a slave and takes the role of mediator in brokering his return to Philemon’s household. Onesimus means ‘useful’ and was the name given to him by Philemon, who was the ‘pater familias’, the head of the household and one to whom certain status and power is ascribed. In Paul’s time, the slave’s original identity was removed from historical consciousness, and replaced by that given by the patron. So these are the characters that bear witness to the truths that Christ wants to impart. Onesimus goes back with the letter, which would be read out loud. In a sense, all three are being placed on trial, Paul, Onesimus and Philemon. The suspense in the passage is whether Paul’s plea to Philemon for clemency on Onesimus’s behalf would be heard and enacted.

While Paul begins the letter by renouncing his apostolic rights, in Verse 22, he takes them up again.

22 And one thing more: prepare a guest room for me, because I hope to be restored to you in answer to your prayers.

In this beautiful text Paul alludes to the return of Jesus, who will judge the living and the dead. He points to the ultimate consummation of heaven and earth, which are no longer separated. Jesus laid down his life, to mediate for the redemption of souls, only to take it up again through the resurrection. The implication is that Paul will return to judge Philemon and to confirm that he obeyed and did what he was told to do, by taking Onesimus back.

SATS: What impact do you expect it to have on the church in South Africa, and on the wider global church?

BM: The application of Paul’s letter is particularly pertinent to the Southern African context. In Paul’s time slaves shared in the household of their masters, and the word challenges us, as believers today, to consider the role played by domestic helpers and our practice with regards to their social status. Transformation must take place, first, in our home circumstances. In many instances the role of domestic workers in our churches is to take care of the children – thereby replicating the inequality played out in our homes.

In what should be the most liberating space – namely the church – our domestic workers are used instead as a transacting space, replicating the roles entrenched by our Apartheid past. This is not how I believe Jesus intended for his church to act. Salvation in Christ extends to transcending social norms and closing the dividing wall. The fundamental glue that brings people together is the Gospel. In Philemon, it is the Gospel of a warring master and an unfaithful slave, who are bound by the message of Christ, and a quest for truth and reconciliation. While the Gospel is often left in a theoretical realm, it is a message that has an incarnation in the physical realm. Social cohesion asks difficult questions of us, like: When last did you invite your domestic worker to share a meal with you? Or: when, last, did a church have a CEO and domestic worker on the same eldership team?

SATS: Is the Letter to Philemon a letter for our time?

BM: I think it is particularly relevant and challenges us to break social boundaries, so that our practices are consistent with the Gospel that Jesus preached. As believer we should not conform to prescribed social norms. We need to use hospitality, particularly, in our homes to break down social barriers and bring about the new identity in Christ Jesus that Paul so often wrote about.

SATS: How does the paper that you and Kevin will present in Berlin fit into your overall thesis?

BM: Our paper focuses on hospitality as a vehicle, in the Southern African context, for breaking down social inequalities, and breaking into greater equity, and social justice. By breaking bread with fellow believers, no matter what their status, and living a life that is consistent with the Gospel, social equity and justice can result. As Christ’s ambassadors, we should own the narrative of social cohesion.

SATS: What fuels Batanayi in terms of Kingdom purpose?

BM: I am principally a teacher – a Bible teacher. More specifically, I feel called to teach the Bible within the African context. It is commonly said that: “Africa is widely reached in terms of evangelism, but shallow in the depth of discipleship.” I want to be part of changing that, to belong to a community of teachers that bring with them Christ’s message for a transformed continent, and to be part of a social change process that brings healing to the nations.